“The world is full of miserable places. One way of living comfortably is not to think about them or, when you do, to send money.” – Tracy Kidder, Mountains Beyond Mountains

For many of us, particularly here in America, we sometimes equate activism, or at least action, with donating money to causes. What’s wrong with that?, you might ask. Donating money can absolutely be a lifeline for important causes and the organizations that endeavor to create change. Here’s a quote from a good friend of mine who works for a non-profit organization:

“I think [what matters] is how the money is ‘thrown’ so to speak. I work in the nonprofit world–and philanthropy literally saves lives. I think it really depends on how and where the money is invested. It is a complex problem…”

Yes, it is a complex problem: donating money without an understanding of the interested and effected parties and the institutions involved can sometimes actually dig the hole deeper. In other words, philanthropy can just as easily reinforce the “ideology of domination that permeates western culture” (Lorde again) by continuing to fund problematic institutions that are responsible for gender, race, and class oppression throughout the world. So here is the most important distinction I want to convey: philanthropy, or donating money, is NOT the same as social activism though it is frequently offered to us as if it were a way for us to act in a world in which we feel disempowered.

For example, the “Swipe Out Starvation” campaign, which encourages us to spend money on food here to feed the hungry out/over there, encourages us to solve world hunger problems by engaging in more consumerism…which is part of what contributes to so much economic disparity in the world to begin with. While donating money helps those who act on our behalf, it allows us to maintain a safe distance from the people that need our support and resources and from the situations that need real reform – and this can be understood as a form of privilege (just as not having to think about awful social problems like poverty or racism or gender-based violence is also a form of social privilege if we have the luxury of not being directly affected by such issues).

Activism, on the other hand, requires our direct and compassionate involvement with the people, communities, and problems at hand, and a complex understanding of our interconnectedness. In Grassroots: A Field Guide for Feminist Activism, Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards define activism as:

“…consistently expressing one’s values with the goal of making the world more just. We use feminism as our philosophy for that value system; that is, we try to take off the cultural lens that sees mostly men and filters out women and replace it with one that sees all people. We ask, ‘Do our lifestyles reflect our politics?’…An activist is anyone who assesses the resources that he or she has as an individual for the benefit of the common good. With that definition, activism is available to anyone…we are challenging the notion that there is one type of person who is an activist–someone serious, rebellious, privileged, and unrealistically heroic” (xix).

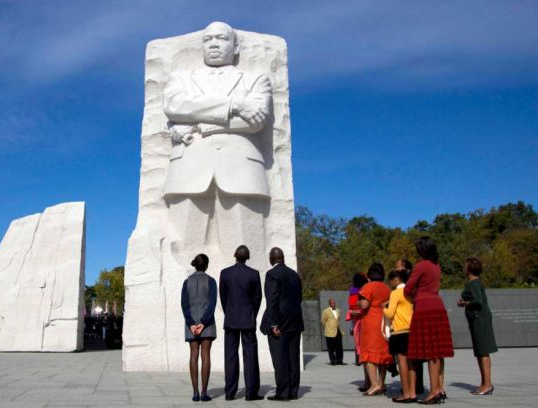

Here, I think back to Mitch Daniels’ speech about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., his introduction to Melissa Harris-Perry’s talk, in which he repeatedly invoked the ideology of the activist or social mover as the one-in-a-million, lone hero. But Harris-Perry began by challenging this ideology, offering a criticism of the new statue of Dr. King, which image draws on that same idea of the individual hero arising out of nothing (neither backed nor supported by anyone in particular).

For Baumgardner and Richards, the activists of the world are not lone individuals, not the ones-in-millions but the millions themselves. Dr. King, Harris-Perry argued, was also one of those millions during his lifetime. He was the voice of a whole movement full of individuals who supported and facilitated his work, and who challenged and shaped his ideas.

ACTIVITY

- Let’s consider Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “The Lovers of the Poor.”

Here’s a quote from Paulo Freire from his famous book Pedagogy of the Oppressed:

“Any attempt to ‘soften’ [or deny] the power of the oppressor [e.g., the wealthy] in deference to the weakness of the oppressed almost always manifests itself in the form of false generosity; indeed, the attempt never goes beyond this. In order to have the continued opportunity to express their ‘generosity,’ the oppressors must perpetuate injustice as well. An unjust social order is the permanent fount of this ‘generosity,’ which is nourished by death, despair, and poverty” (Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 44).

So the women from the Ladies Betterment League in Brooks’ poem unwittingly contribute to perpetuating the injustice of the poverty that they claim to generously aid; both the oppressors (here, the well-meaning wealthy women) and the oppressed (the poor living in slums) are caught in and ultimately dehumanized by this “charitable” interaction. While charity reinforces the idea of the privileged who “come down” to help the less fortunate, thereby demonstrating their own goodness, social activism works to help us realize the no one is served unless we are all served equally, unless we all have equal access to basic rights and resources.

So it’s deeply problematic, for example, whenever we enter into philanthropy with the mindset of “helping the less fortunate” without also calling into question how we may be part of or complicit in a system that ultimately keeps us separate from them, or that maintains a divide between the haves and the have-nots.